Xanadu, a term representing a luxurious or idyllic place—much like "Shangri-La" or "paradise" in English—was the name of the summer capital of Kublai Khan’s empire. Its name entered the English language through the Venetian traveler Marco Polo, who stood awestruck before its gilded halls, describing it as "a palace of marvel… all covered with gold and silver."

In 1797, Xanadu famously appeared in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem Kubla Khan, inspired by an opium-induced dream and Polo’s vivid descriptions. The opening lines—"In Xanadu did Kubla Khan / A stately pleasure-dome decree"—immortalized the name in Western literature.

Few people realize, however, that Xanadu was a real place. The name is actually a misspelling of Xandu, (Shangdu 上都, "Upper Capital"), located in present-day Zhenglan Banner, Inner Mongolia, China. Today, the ruins of Xanadu still lie in the vast grasslands, a silent testament to the grandeur of the Mongol Empire.

The Yuan: A Dynasty with the Mandate of Heaven

In traditional Chinese historiography, Kublai Khan conquered the Song Dynasty in 1279 and founded the Yuan Dynasty, establishing its capital in Dadu (大都, "Grand Capital"), present-day Beijing. The Yuan reunified China as a single state, ending the prolonged fragmentation that had persisted since the fall of the Tang Dynasty in 907 (corrected from 968). Ultimately, the Yuan was overthrown by the Ming Dynasty due to the corruption of the Mongol ruling elite.

After the Ming toppled the Yuan in 1368, they initially denounced the Mongols as "barbarian invaders" while paradoxically inheriting much of their administrative framework—including provincial systems, land registries, and even Beijing’s urban layout. To reconcile this contradiction, Confucian scholars later legitimized the Yuan as Zhengtong (正統, "orthodox succession"), arguing: "Those who govern virtuously inherit the Mandate of Heaven—irrespective of origin." This pragmatic stance transformed foreign conquerors into rightful rulers. The Manchu Qing Dynasty later adopted the same strategy when they came to power.

Today, the Mongol legacy endures in Beijing—from the white stupas of Beihai Park and the lakes of Shichahai to Hui Muslim noodle shops serving Central Asian-inspired dishes.

Twin Capitals and the Imperial Road (Nianlu)

When Kublai Khan established Xanadu in 1256, he created a cultural fusion. Han-style temples honoring Confucius stood alongside Tibetan Buddhist shrines, while Mongol yurts clustered near marble palaces, and eagle hunts continued across the steppes. Most significantly, Xanadu's central axis aligned precisely with Beijing's - a symbolic tether connecting the nomadic north to the agrarian south.

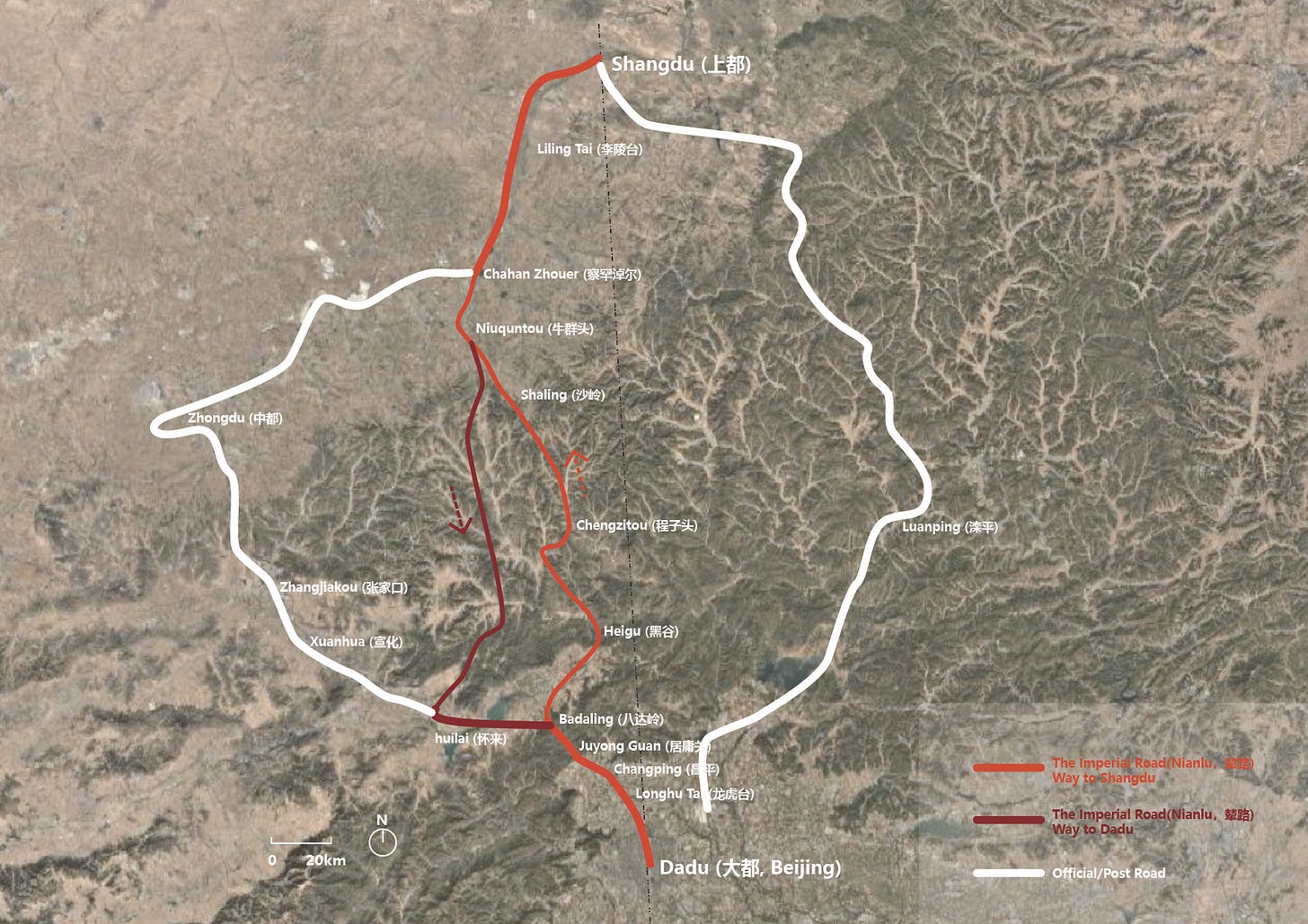

In 2016, Peking University historian Luo Xin embarked on a 450-kilometer journey from Beijing to Xanadu's ruins in Inner Mongolia. His 15-day trek, documented in the book From Dadu to Shangdu, retraced the ancient Nianlu (辇路) - the imperial road where Yuan emperors traveled between their summer capital (Xanadu) and winter seat of power (Dadu, modern Beijing). The Yuan transportation system maintained strict hierarchies: while privileged Mongol aristocrats could accompany the emperor on the Nianlu, other officials had to use the separate official road alongside commoners.

The imperial road embodies a living collision of histories. After Kublai Khan established Dadu (Beijing), he institutionalized seasonal migrations between Dadu and Shangdu for the Yuan emperors and their court—preserving Mongol nomadic traditions while governing a settled empire.

When the Ming toppled the Yuan, the Mongols retreated northward, reclaiming pastoral nomadism and becoming persistent adversaries to the Ming. With Beijing remaining the capital, the Ming fortified the mountain passes with brick Great Walls, shaping the defensive layout we recognize today. The Nianlu became a frontline between agrarian and pastoral worlds—where war and trade intertwined. Mongols defected to Ming border towns for sustenance, while peasants fled north to escape taxes and persecution. Through it all, cultural fusion persisted beyond the Wall’s barriers.

Evidence of this synthesis survives at Juyong Pass, where a massive stupa base, Cloud Platform,bears the Dhāraṇī Sutra(《陀罗尼经咒》) inscribed in six scripts: Tibetan, Sanskrit, Chinese, Phags-pa, Uyghur, and Tangut.

Today, this ancient path threads through Great Wall tourists, Beijing weekenders, and cornfields where emperors once planned conquests. Mongol horsemen, Ming sentries, and modern farmers have shared these coordinates across eras—each inhabiting parallel worlds.

Xanadu: Fantasy vs. Reality

Historical memories of the Mongol Empire exhibit striking regional variations. China integrates the Yuan Dynasty into its orthodox dynastic narrative while emphasizing ethnic integration, whereas Japan preserves the "divine wind" legend as anti-Mongol war memory. The Islamic world reflects a duality of trauma and acceptance—Persian chronicles meticulously document the fall of Baghdad, while the Mamluk victory at Ain Jalut became an epic triumph in Arab consciousness. European perspectives diverge sharply: Eastern European nations view Mongol invasions as national tragedies, Russian Eurasianists emphasize the Golden Horde's role in state centralization, and Western Europe maintains contradictory Marco Polo-inspired tropes of Mongol "Eastern wealth" alongside "Yellow Peril" anxieties. These mnemonic differences derive not only from distinct historical experiences but also from selective narratives in modern nation-state building.

In 1986, two Cambridge undergraduates retraced Marco Polo's route from Cyprus through the Middle East and Central Asia to China's Xinjiang, proceeding along the Hexi Corridor to Beijing and ultimately Shangdu (Xanadu). Believing themselves the first Europeans since Stephen Bushell—the English physician and amateur Orientalist who documented the ruins in 1872—they relied solely on his 19th-century account as their guide. William Dalrymple, one of the travelers, later immortalized this 12,000-mile journey in his book In Xanadu. Detained at Zhenglan Banner for inadequate travel permits, they were granted a brief visit to the ruins after a Mongolian official, moved by their dedication to Kublai Khan's legacy, rerouted their deportation.

For centuries, China has served as a symbolic construct in the Western imagination, and even today it continues to function as an ancient yet persistently mysterious cultural icon. In 1988, performance artists Marina Abramović and Ulay undertook their seminal work "The Lovers: The Great Wall Walk," a durational piece that saw them trekking 2,500 km from opposite ends of the Great Wall over 90 days - Ulay starting from the western Gobi Desert while Abramović began at the eastern Yellow Sea. Their poignant convergence at a Buddhist temple in Shenmu, Shaanxi Province culminated in a final embrace that marked not only the end of their 12-year romantic and artistic partnership but also created a powerful ritual of separation, more elegiac than celebratory in nature.

The Western fascination with Chinese symbols and their reinterpretation of China's narrative has even influenced how Chinese people perceive their own history. The Great Wall, once primarily a symbol of the pain and forced labor embodied in the Meng Jiangnü myth (where a weeping widow's tears were said to crumble sections of the Wall), has been transformed through Western perspectives into a more positive or neutral national icon - a transformation eventually adopted by China itself.

As for Xanadu, I had long been aware of the Shangdu ruins as just one among China's many archaeological sites. However, when I realized that this was the Xanadu of Coleridge's poetic imagination, I felt compelled to visit. The site, known in Chinese as 金莲川 (Golden Lotus Plains), suddenly transcended its physical remains to become a bridge between historical reality and literary legend.

The Nianlu’s Whisper: Rediscovering "Chineseness"

Luo Xin's journey reveals history's living layers. At Juyongguan Fortress, Yuan dynasty inscriptions intermingle with Qing-era graffiti. Across Inner Mongolia's grasslands, Han farmers and Mongol herders still share milk tea—a centuries-old ritual of cultural coexistence.

China's identity wasn't forged behind static walls, but along dynamic routes like the Nianlu—where Mongol cavalry, Ming border troops, and modern migrant workers exchanged goods, genes, and worldviews across eight centuries.

The West's romantic "Xanadu" fantasy isn't incorrect—just incomplete. Every civilization requires utopias. But as Luo's foot blisters attested, history is inscribed by calloused feet on dusty trails, not through poetic dreams. For China, the Yuan represents neither foreign interruption nor sterile textbook category. This illustrates how "Chineseness" has dynamically evolved - shaped by Mongolian traditions and Han agricultural practices - transcending the physical boundaries of the Great Wall through centuries of interaction.

(This article was inspired by Luo Xin's From Dadu to Shangdu. Highly recommended for those interested in the historical geography around Beijing !)